clear: slight breeze: 87ºF

clear: slight breeze: 87ºF

Today is opening day for one of this botanical garden’s big events: the Japanese Festival. This marks the 36th year of annual Labor Day weekend event. Crowds are a given. Last year the event drew 35,000 visitors. However with a forecast of 100+ temperatures for today, a lot of the expected visitors seem to be staying away. I noticed that even at 11:00 a.m., no one was waiting in line to buy tickets.

Every year the Festival has a theme. This year it’s the lotus. Festival t-shirts and programs all have a lotus graphic. Appropriately, the Garden has a patch of lotus of growing at the edge of the lake that’s the centerpiece of its Japanese Garden. The program for the Festival says that the lotus is a significant part of Japanese culture: “The lotus spreads its roots in the mud at the bottom of a pond, then its stems push up to the surface, where the flower emerges, pristine and white, reflecting Buddhist thoughts about struggling through life’s difficulties to emerge in the pureness of enlightenment.” Nice thought. We can come through life’s shit unscathed.

Still the lotus plot in the Japanese Garden does have its limits. There’s a metal barrier that stops the roots from spreading and becoming invasive. A good example of what happens when lotus is allowed to spread at will is this lake I saw a week ago at the August A. Busch Memorial Conservation Area just outside of town. Lotus, uncontrolled and unrestrained, is smothering the lake. Makes me wonder if there’s such a thing as too much enlightenment.

New to me—pedestal fans that spray a trail of mist. Anticipating the hot weather, the festival planners have placed misting fans all over the Garden. I walked through one placed just inside the entrance to the Garden. It doused my t-shirt and cooled my face. Within the envelope of spray carried outward by the fan, the temperature felt as though it had dropped 20 degrees.

The Japanese Festival always draws teenagers who come with a date or with a group of friends. Some come dressed in stylized military outfits; more wear baby pink or polka-dot skirts or sidewalk-dragging gowns. Jet-black, two-toned, or orange wigs are popular too. A hour or more before opening, there was a long line of young people waiting to get into the Garden’s auditorium to see a Cosplay fashion show. Cosplay, short for costume play, is described in the Festival program dressing up as a character from a film, book, video game or comic book and then acting and talking as that character might. I wish we had stayed to see the show when I got home are read this in the program: “We welcome all cosplays to the Festival, but please leave your weapons at home, even if they are harmless props, and make sure that your costumes are family appropriate.”

Who chooses a hosta for its flowers? With hostas, the leaf’s the thing. Some hosta growers think the flowers are a distraction so they cut down the flower stocks as soon as they appear – better to see your leaves, my dear. Yet late summer brings out some pretty spectacular flowering hostas. The best of the lot is

Hosta plantaginea.

Plantagineas produce plenty of oversized white blooms with a scent that could understudy an oleander. For plentiful, interestingly shaped blooms, there’s this one with skinny purple petals. It’s a species hosta named

Hosta yingeri that was discovered on an island off the coast of South Korea about 25 years go. My Hosta Handbook says “it created quite a stir” when it was introduced. As the first new hosta species discovered in many years, it was looked upon as a source of new genetic material for breeding.

This is a good time to see hummingbirds and butterflies in the garden. I don’t know if they’re local residents or whether they’re just passing through on their way South. I like finding a bench near some flowers and just watching the passing parade. This zinnia is hosting a swallowtail.

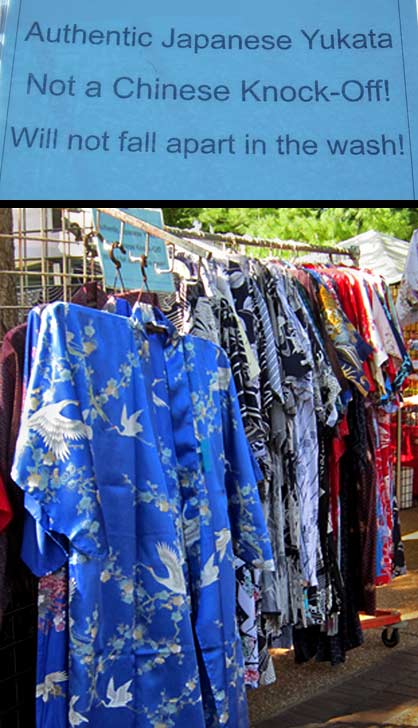

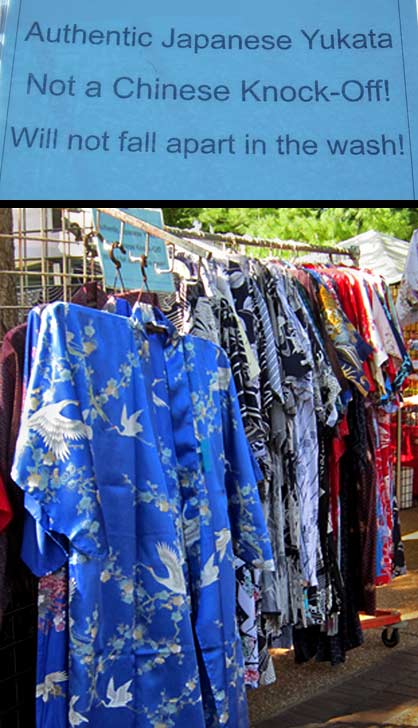

I saw this sign attached to these racks of colorful Yukata. Curious how many things sold here at this Japanese Festival are made in China.

clear: very little stirring: 74ºF

clear: very little stirring: 74ºF

Edibles is the theme of this summer. Instead of giving visitors who enter the botanical garden a ravishing display of tropical colors and exotic leaves, they get instead a line of display gardens that look like a lot in an untended vacant property. Unless they’re taking pictures of the water lilies in the ponds surrounded by the edibles, most photographers steer clear of these plots to get to more picturesque parts of the Garden.

In the edible gardens are sugar cane, okra, fennel, and sorgum, stivia, and chicory -- those I know. Back in my Euell ‘Stalking the Wild Aspargus’ Gibbons days, I even dug, dried, roasted, and ground chicory to make coffee. Some of the edibles planted here are unfamiliar though. Marsh Mallow (

Althaea officinalis) is new to me. At first glace it looks like a hollyhock – it’s tall, 3-5 feet high; it forms clumps of buds; and it has hairy leaves. Flowers though are small – white with a purple-red tube inside. What makes this plant interesting is that it’s the real thing -- this is the plant that was used for centuries to make marshmallows until it was bumped aside by corn starch and gelatin. An identifying sign nearby says that marshmallow treats date back to the ancient Egyptians who extracted the sap from marsh mallow roots and mixed it with nuts and honey.

Another plant I knew nothing about was Roselle (

Hibiscus sabdariffa). It’s a short, bushy, leafy plant that reminds me a bit of a cotton plant. Roselle grows year around in zones far south of our 6b. It’s supposed to produce yellow flowers but I haven’t seen any in bloom yet. A nearby sign says that once the flowers bloom and fall off the calyx –the arrangement at the base flower that supports the flower – it will enlarge and

grow into a red pod to protect the maturing seeds. That red pod is the interesting part. When dried, it can be used to make a red tea that has a tart cranberry taste. Likely it’s part of the blend that makes Red Zinger, my wintertime favorite:

Celestial Seasons says about Red Zinger: “The zing comes from a blend of tart and tangy Chinese hibiscus and fruity Thai hibiscus, balanced by cool, refreshing peppermint and the unique, earthy sweetness of wild cherry bark.”

When camellias are out of season, I look for the Franklin tree (

Franklinia alatamaha). There’s one in bloom right now in the scented garden. Its blossoms look like a camellia, but unlike a camellia, it’s said to be very fragrant. This morning it wasn’t. No known Franklin trees have been seen in the wild for more than 200 years. But because 18th Century botanist John Bartram happened upon the trees during a expedition to Georgia and collected some plants and seeds, the tree still lives today. Bartram’s garden where he planted the Franklin Tree and many other plants he collected on his travels was the first botanical garden in the country. It’s 30 miles away from the arboretum Peirces – the site of Longwood Gardens. Both men were Quakers. Both Bartham and Peirce shared the Quaker belief that understanding the natural world was way of understanding God.

New varieties of coleus continue to be developed. Three fine ones are being shown inside the Linnean glasshouse. Because they’re growing inside they’ll stay in prime condition all season long. They’re planted in large container pots close to the walkway so that visitors can get very close. Here are three of them. First, ‘Honey Crisp,’ a yellow with green flecks, and rose-color edges and undersides. Next, ‘Redhead’ and finally ‘Dipt in Wine.’

Just outside the staircase leading up to the building (now closed) that was built in 1859 to house Henry Shaw’s herbarium and natural history museum, I saw this. I must have seen it or passed it dozens of times but this morning was the first time I’d noticed it and then wondered about it. After doing a match image search on Google, I got some hits. Turns out it's a

Victorian era boot scraper. Either etiquette or house rules must have called for gentleman of the day to scrape before entering the museum.

Here’s another curious object that’s been appearing all over the botanical garden during the summer. No signs anywhere to explain what it is or what it’s supposed to do. Google image match doesn’t know either. The white objects are made of light plastic. They’re mounted on poles about four feet off the ground. Inside there are no moving parts, no electronic connections – just a dark-colored rod in the middle. Ideas??

Who but the keepers of a botanical garden would think of using a tropical plant from West Africa as the centerpiece of a container planting? This striking four-foot tall shrub is labeled ‘Red Flag’ (

Mussaenda erythrophilla). My garden’s book calls it ‘Ashanti Blood.’ The common names come from the deep red bracts arranged in a toothy array around cream-colored flowers which were still in bud this morning.

Just as we’ve grown to expect to see strawberries in stores all year long, so too do we want to have shrubs that bloom out-of-season. Longwood Gardens is still working a camellia that will start to bloom when others have stopped. However, season-extender azaleas are already here. One planted in a shady spot in the English Garden is called ‘Conlep’ AUTUMN TWIST. The developer has named ‘Conlep’ and others like it ‘Encore Azeleas’ because they bloom in the spring along with all the other azaleas and then go to bloom again in the summer and fall. This Encore has large white flowers with orchid-colored stripes and spots.

a few passing clouds over a blue sky: calm : 72ºF

a few passing clouds over a blue sky: calm : 72ºF

Longwood Gardens – one of those fabled gardens that I’ve wanted to visit, but until today never had. It’s near enough to most cities in the New York to Washington corridor to attract a million visitors a year, but far enough from me here in the Midwest to make any visit seem exotic.

As savvy as the plant people at Longwood are about choosing, growing, and displaying plants from every part of the world, Longwood doesn’t bill itself as a “botanical garden.” Unlike the mission statements of botanical gardens that are loaded with words like research, conservation, sustainability, and preservation, Longwood Gardens says it’s here to delight people. So instead of plants being the reason for its existence, at Longwood Gardens plants are a means of conveying beauty and pleasure to all who visit. Longwood sees its niche as “. . . inspiring people through excellence in garden design, horticulture, education, and the arts” and to “present the arts in an unparalleled setting to bring pleasure and inspire the imagination of our guests.” Pierre du Pont, the Garden’s founder, said he wanted “to grow ordinary plants extraordinarily well, and Longwood has ravishing displays of the best chosen for aesthetic rather than botanical interest.”

To pay for all this beauty the Gardens depend on money from the endowment and the foundation setup by du Pont and from admissions, rentals, programs, and income from its gift shop and restaurant. A sign along one of the walkways says that the Garden receives no government money.

I like looking at beginnings. How and why do gardens like Longwood Gardens get started? Like many botanical gardens, Longwood started with one person. Here it was Pierre du Pont. Du Pont was many things: scion of the du Pont line, head of du Pont chemicals, chairman of GM, and philanthropist on a grand scale.

The land where Longwood is today was owned by the Peirce family whose ancestors bought it from William Penn to farm. The next two generations of the family planted an arboretum and made a park with pleasure gardens, croquet courts, summerhouses and rowboats that welcomed the public. Later generations had no interest in the park or the collection of trees so by 1900 the park was closed. du Pont bought the property in 1906. He said he bought the land to have a place where he could entertain his friends as well as to save the century-old arboretum from being cut for lumber.

Like Henry Shaw, founder of the Missouri Botanical Garden where I walk, Pierre du Pont got some his best ideas about plants and gardens during his travels to world fairs and to the parks and villas he visited in Europe. When he built Longwood Gardens, he remembered his fascination with the fountains, conservatories, theaters, spectacles, and gardens that he saw on those trips.

Longwood Gardens opened in 1921 and now has 1000+ acres, 350 of which are open to visitors. I had just five hours to see Longwood. So before arriving I checked the Garden’s website looking for the must-dos: the conservatory, of course. With 4.5 acres under glass and 20 rooms of themed gardens, a grand ballroom, and a 10,000 pipe organ, it had to be the first stop . Next, the main fountains just south of the conservatory’s promontory overlook. They’re meant to dazzle with light shows at night and choreographed water dances during the day. Finally, I wanted to see the popular display of Victoria water lilies.

Along the broad walkway leading the Conservatory is an allee of Paulownia tomentosa trees. The botanical garden where I usually walk has two of these ‘Princess’ trees. In the spring, they have tight clusters of orchid-colored flowers that light up the tree. Until today though, I thought these trees were novelties. They don't grow straight and they have branches that appear helter-skelter. But they do grow fast – up to 12 feet a year I’ve read. That makes them useful for quick-fix landscaping in places like restored strip mines.

Along the broad walkway leading the Conservatory is an allee of Paulownia tomentosa trees. The botanical garden where I usually walk has two of these ‘Princess’ trees. In the spring, they have tight clusters of orchid-colored flowers that light up the tree. Until today though, I thought these trees were novelties. They don't grow straight and they have branches that appear helter-skelter. But they do grow fast – up to 12 feet a year I’ve read. That makes them useful for quick-fix landscaping in places like restored strip mines.

Unlike the Princess trees I’m used to seeing the trees along this alee are shapely and polite-looking just as I’d expect any street tree should look. They all have straight, single trunks about a foot around.

How do they do that I wondered? Aside from a man on rider lawnmower, there was no one to ask. Later I found a website written by a couple of guys who saw what I saw and found out how the Longwood gardeners got the Princess trees to behave so well. The guys, Mark and Dave, talked with a Longwood staffer who told them that the trees were planted about 15 years ago but they grew crooked and misshapen. So they were all cut down. Then the stump and roots were allowed to grow new shoots. Finally the shoots were thinned to one true stem. With regular pruning and shaping, the trees grew straight and tall. Mark and Dave’s website have some great pictures of the Longwood’s shapely Princess trees in winter.

Next stop: the Conservatory. It’s been described as having the face of Victorian orangery combined with peaked glass roof of an greenhouse. It reminded me a bit of the pictures I’ve seen of Horticultural Halls that were always a part of world fairs in the 19th Century.

Inside, this place is like none I’d ever seen. Conservatories in botanical gardens usually are focused on saving space. They’re heavily planted – intent on finding a space for every exotic specimen they can squeeze in. Instead here at Longwood visitors are greeted with a view of an expansive lawn. Grass, common everyday grass, definitely not exotic grass. Here space doesn’t matter. There’s enough to go around for the ordinary and the unusual.

Inside, this place is like none I’d ever seen. Conservatories in botanical gardens usually are focused on saving space. They’re heavily planted – intent on finding a space for every exotic specimen they can squeeze in. Instead here at Longwood visitors are greeted with a view of an expansive lawn. Grass, common everyday grass, definitely not exotic grass. Here space doesn’t matter. There’s enough to go around for the ordinary and the unusual.

I look at camellias every chance I get. So even though I knew they wouldn’t be blooming at this time of year, I headed first to the Camellia Room. Longwood horticulturalists have some interesting research going on here. They’re trying to breed an ever-blooming camellia. They’ve started with a rare camellia named Camellia Azalea that was discovered in southeastern China about 25 years ago. While it’s reported to bloom from March through December and is able to flower even in temperatures that top 90 degrees, it does make some finicky demands that make it hard to propagate and grow.

Since other varieties of camellias bloom from November through March and flower best when temperatures are cool, Camellia Azalea could be a breakthrough if it could be used as breeding stock. Researchers at Longwood Gardens have been working for more than a decade to develop a hybrid camellia that’s easy to grow and propagate and that produces big, beautiful flowers all year long in a variety of growing zones. The holy grail – akin to that elusive, yet to be seen, blue rose. This is a picture of a Camellia japonica that’s been crossed with a Camellia azalea with pod covered to preserve the developing seeds.

Since other varieties of camellias bloom from November through March and flower best when temperatures are cool, Camellia Azalea could be a breakthrough if it could be used as breeding stock. Researchers at Longwood Gardens have been working for more than a decade to develop a hybrid camellia that’s easy to grow and propagate and that produces big, beautiful flowers all year long in a variety of growing zones. The holy grail – akin to that elusive, yet to be seen, blue rose. This is a picture of a Camellia japonica that’s been crossed with a Camellia azalea with pod covered to preserve the developing seeds.

Amazing, yet odd – the “Green Wall” that’s across the entrance from the Camellia Room. Amazing because it holds the record for the longest living wall in the country -- 14 feet tall and plugged with ferns and common houseplants that lead down a curving corridor.Odd because its function seems to be to disguise what otherwise could have been a stark hallway with nondescript white doors on both sides that open into individual restrooms so large, so clean, so elegant that they deserve to be called comfort stations.

function seems to be to disguise what otherwise could have been a stark hallway with nondescript white doors on both sides that open into individual restrooms so large, so clean, so elegant that they deserve to be called comfort stations.

Somewhere I read that Pierre du Pont was disappointed with vigor and spent look of some Australian tree ferns that he saw in a conservatory that he visited on his travels. He vowed if he ever got the chance, he could do better. Humidity is the key. So to accommodate their needs he built this sunken garden near the ballroom. The marble floor is usually flooded to provide the humidity the ferns need.

Somewhere I read that Pierre du Pont was disappointed with vigor and spent look of some Australian tree ferns that he saw in a conservatory that he visited on his travels. He vowed if he ever got the chance, he could do better. Humidity is the key. So to accommodate their needs he built this sunken garden near the ballroom. The marble floor is usually flooded to provide the humidity the ferns need.

On the south side of the conservatory there’s a promenade overlook for viewing the fountain displays. Every couple of hours the fountains put on a five-minute show. Visitors who get to the overlook early take the center spots and sit on cast iron chairs that look as though they’d be at home at a garden party in Victorian times. Late comers sit on wooden bleachers off to the side.

The show itself didn’t dazzle me. Water spouted high; jets turned inward to cause an cloud of mist; and finally water from the central jet jutted even higher. Then it was over. No one even applauded as they scurried to the restaurant to have lunch. Perhaps fountain displays no longer have the power to astonish visitors today and they did at the world fairs of the 1800s. Then again, perhaps I needed get closer to the fountains before I could feel the majesty and power of the display. The overlook is about a quarter mile away from the dancing waters.

Today, the outdoor water lily display seemed to draw the biggest crowds. For good reason. In addition to a collection of colorful tropical water lily hybrids, the display also has the big three of the giant Victoria water platters – Victoria amazonica, Victoria cruzina, and the one developed fifty years ago here at Longwood Gardens: Victoria x ‘Longwood Gardens.’

For visitors like me who like to get close to plants, this water lily display is ideal. Some of the Victorias were so close to the edge of the pool that I could have reached out and felt the spikes along the side of their pads.

For visitors like me who like to get close to plants, this water lily display is ideal. Some of the Victorias were so close to the edge of the pool that I could have reached out and felt the spikes along the side of their pads.

In the Exhibit Hall near the water lily ponds, there was an exhibit that traced the history of the Victorias. When the Victoria amazonica was first seen in 1837 by a explorer and amateur botanist who happened upon it in a remote part of British Guiana he wrote, “A vegetable wonder! All calamities are forgotten.” The popularity of the plant took off when clever promoters got royal consent to have the lily named Victoria Regia in honor Queen Victoria. The design of the underside of the pads even inspired the architecture of London’s Crystal Palace built for the Great Exhibition of 1851.

Included in the exhibit is this photograph of a colony of Victoria water lilies taken from space. A nearby sign says that the Victoria is the only plant on earth that can be identified from satellite imagery.

Included in the exhibit is this photograph of a colony of Victoria water lilies taken from space. A nearby sign says that the Victoria is the only plant on earth that can be identified from satellite imagery.

The Longwood hybrid was developed in 1960 when a team of water lily experts got together at Longwood to cross Victoria cruzina with Victoria amazonica. The result was a cross that had larger pads with higher rims, deeper redder colors, better germination rates, and better tolerance to colder water.

And here are some pictures of some of other photogenic tropical water lilies growing in the display ponds:

The least visited part of the Conservatory seemed to be the glass houses used to grow fruits. During du Pont’s time an entire wing of the Conservatory was in fruit production. Now there are just a couple of narrow houses. du Pont’s favorites were nectarines, but he also grew apricots, peaches, grapes and figs. In the days when being able to eat out-of-season fruit was a rarity, du Pont was able to surprise his friends by sending them gift boxes filled with out-of-season fruit he raised in his greenhouses. Judging from this comment I read from one of his gardeners who tended his vineyard in 1920, the fruit du Pont ate and sent had to be just right: “When the cluster of grapes was still green and the individual grapes were about the size of peas, we would take a pair of manicure scissors and go through each cluster and thin it out so that the distance between grapes was no closer than ¾ of an inch.”

All of the fruit trees and grape vines are trained to grow on vertical trellises to make them easier to harvest and to get an increased yield in a smaller space.

All of the fruit trees and grape vines are trained to grow on vertical trellises to make them easier to harvest and to get an increased yield in a smaller space.

I left Longwood thinking that there’s a fuzzy line between gardens that call themselves botanical and those that don’t. Read a botanical garden’s mission statement and there’s sure to be words like research, conservation, and education. Places like parks or pleasure gardens use plants, usually showy ones arranged in mass plantings, to create pleasant, landscaped places where people can relax, stroll, talk, clear their minds, or refresh their spirits. Longwood doesn’t call itself a botanical garden but yet it does research, it labels all of its plants with their botanical names, it has educational exhibits, and has many exotic plants that would be the envy of some botanical gardens. As I was leaving I felt this was the kind of Garden that visitors would come away from feeling satisfisfied and rewarded even if they never looked at a plant label or read a single explanatory sign.

Every year the Festival has a theme. This year it’s the lotus. Festival t-shirts and programs all have a lotus graphic. Appropriately, the Garden has a patch of lotus of growing at the edge of the lake that’s the centerpiece of its Japanese Garden. The program for the Festival says that the lotus is a significant part of Japanese culture: “The lotus spreads its roots in the mud at the bottom of a pond, then its stems push up to the surface, where the flower emerges, pristine and white, reflecting Buddhist thoughts about struggling through life’s difficulties to emerge in the pureness of enlightenment.” Nice thought. We can come through life’s shit unscathed.

Every year the Festival has a theme. This year it’s the lotus. Festival t-shirts and programs all have a lotus graphic. Appropriately, the Garden has a patch of lotus of growing at the edge of the lake that’s the centerpiece of its Japanese Garden. The program for the Festival says that the lotus is a significant part of Japanese culture: “The lotus spreads its roots in the mud at the bottom of a pond, then its stems push up to the surface, where the flower emerges, pristine and white, reflecting Buddhist thoughts about struggling through life’s difficulties to emerge in the pureness of enlightenment.” Nice thought. We can come through life’s shit unscathed.

New to me—pedestal fans that spray a trail of mist. Anticipating the hot weather, the festival planners have placed misting fans all over the Garden. I walked through one placed just inside the entrance to the Garden. It doused my t-shirt and cooled my face. Within the envelope of spray carried outward by the fan, the temperature felt as though it had dropped 20 degrees.

New to me—pedestal fans that spray a trail of mist. Anticipating the hot weather, the festival planners have placed misting fans all over the Garden. I walked through one placed just inside the entrance to the Garden. It doused my t-shirt and cooled my face. Within the envelope of spray carried outward by the fan, the temperature felt as though it had dropped 20 degrees. Who chooses a hosta for its flowers? With hostas, the leaf’s the thing. Some hosta growers think the flowers are a distraction so they cut down the flower stocks as soon as they appear – better to see your leaves, my dear. Yet late summer brings out some pretty spectacular flowering hostas. The best of the lot is Hosta plantaginea. Plantagineas produce plenty of oversized white blooms with a scent that could understudy an oleander. For plentiful, interestingly shaped blooms, there’s this one with skinny purple petals. It’s a species hosta named Hosta yingeri that was discovered on an island off the coast of South Korea about 25 years go. My Hosta Handbook says “it created quite a stir” when it was introduced. As the first new hosta species discovered in many years, it was looked upon as a source of new genetic material for breeding.

Who chooses a hosta for its flowers? With hostas, the leaf’s the thing. Some hosta growers think the flowers are a distraction so they cut down the flower stocks as soon as they appear – better to see your leaves, my dear. Yet late summer brings out some pretty spectacular flowering hostas. The best of the lot is Hosta plantaginea. Plantagineas produce plenty of oversized white blooms with a scent that could understudy an oleander. For plentiful, interestingly shaped blooms, there’s this one with skinny purple petals. It’s a species hosta named Hosta yingeri that was discovered on an island off the coast of South Korea about 25 years go. My Hosta Handbook says “it created quite a stir” when it was introduced. As the first new hosta species discovered in many years, it was looked upon as a source of new genetic material for breeding. This is a good time to see hummingbirds and butterflies in the garden. I don’t know if they’re local residents or whether they’re just passing through on their way South. I like finding a bench near some flowers and just watching the passing parade. This zinnia is hosting a swallowtail.

This is a good time to see hummingbirds and butterflies in the garden. I don’t know if they’re local residents or whether they’re just passing through on their way South. I like finding a bench near some flowers and just watching the passing parade. This zinnia is hosting a swallowtail.

In the edible gardens are sugar cane, okra, fennel, and sorgum, stivia, and chicory -- those I know. Back in my Euell ‘Stalking the Wild Aspargus’ Gibbons days, I even dug, dried, roasted, and ground chicory to make coffee. Some of the edibles planted here are unfamiliar though. Marsh Mallow (Althaea officinalis) is new to me. At first glace it looks like a hollyhock – it’s tall, 3-5 feet high; it forms clumps of buds; and it has hairy leaves. Flowers though are small – white with a purple-red tube inside. What makes this plant interesting is that it’s the real thing -- this is the plant that was used for centuries to make marshmallows until it was bumped aside by corn starch and gelatin. An identifying sign nearby says that marshmallow treats date back to the ancient Egyptians who extracted the sap from marsh mallow roots and mixed it with nuts and honey.

In the edible gardens are sugar cane, okra, fennel, and sorgum, stivia, and chicory -- those I know. Back in my Euell ‘Stalking the Wild Aspargus’ Gibbons days, I even dug, dried, roasted, and ground chicory to make coffee. Some of the edibles planted here are unfamiliar though. Marsh Mallow (Althaea officinalis) is new to me. At first glace it looks like a hollyhock – it’s tall, 3-5 feet high; it forms clumps of buds; and it has hairy leaves. Flowers though are small – white with a purple-red tube inside. What makes this plant interesting is that it’s the real thing -- this is the plant that was used for centuries to make marshmallows until it was bumped aside by corn starch and gelatin. An identifying sign nearby says that marshmallow treats date back to the ancient Egyptians who extracted the sap from marsh mallow roots and mixed it with nuts and honey. Another plant I knew nothing about was Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa). It’s a short, bushy, leafy plant that reminds me a bit of a cotton plant. Roselle grows year around in zones far south of our 6b. It’s supposed to produce yellow flowers but I haven’t seen any in bloom yet. A nearby sign says that once the flowers bloom and fall off the calyx –the arrangement at the base flower that supports the flower – it will enlarge and grow into a red pod to protect the maturing seeds. That red pod is the interesting part. When dried, it can be used to make a red tea that has a tart cranberry taste. Likely it’s part of the blend that makes Red Zinger, my wintertime favorite: Celestial Seasons says about Red Zinger: “The zing comes from a blend of tart and tangy Chinese hibiscus and fruity Thai hibiscus, balanced by cool, refreshing peppermint and the unique, earthy sweetness of wild cherry bark.”

Another plant I knew nothing about was Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa). It’s a short, bushy, leafy plant that reminds me a bit of a cotton plant. Roselle grows year around in zones far south of our 6b. It’s supposed to produce yellow flowers but I haven’t seen any in bloom yet. A nearby sign says that once the flowers bloom and fall off the calyx –the arrangement at the base flower that supports the flower – it will enlarge and grow into a red pod to protect the maturing seeds. That red pod is the interesting part. When dried, it can be used to make a red tea that has a tart cranberry taste. Likely it’s part of the blend that makes Red Zinger, my wintertime favorite: Celestial Seasons says about Red Zinger: “The zing comes from a blend of tart and tangy Chinese hibiscus and fruity Thai hibiscus, balanced by cool, refreshing peppermint and the unique, earthy sweetness of wild cherry bark.” When camellias are out of season, I look for the Franklin tree (Franklinia alatamaha). There’s one in bloom right now in the scented garden. Its blossoms look like a camellia, but unlike a camellia, it’s said to be very fragrant. This morning it wasn’t. No known Franklin trees have been seen in the wild for more than 200 years. But because 18th Century botanist John Bartram happened upon the trees during a expedition to Georgia and collected some plants and seeds, the tree still lives today. Bartram’s garden where he planted the Franklin Tree and many other plants he collected on his travels was the first botanical garden in the country. It’s 30 miles away from the arboretum Peirces – the site of Longwood Gardens. Both men were Quakers. Both Bartham and Peirce shared the Quaker belief that understanding the natural world was way of understanding God.

When camellias are out of season, I look for the Franklin tree (Franklinia alatamaha). There’s one in bloom right now in the scented garden. Its blossoms look like a camellia, but unlike a camellia, it’s said to be very fragrant. This morning it wasn’t. No known Franklin trees have been seen in the wild for more than 200 years. But because 18th Century botanist John Bartram happened upon the trees during a expedition to Georgia and collected some plants and seeds, the tree still lives today. Bartram’s garden where he planted the Franklin Tree and many other plants he collected on his travels was the first botanical garden in the country. It’s 30 miles away from the arboretum Peirces – the site of Longwood Gardens. Both men were Quakers. Both Bartham and Peirce shared the Quaker belief that understanding the natural world was way of understanding God.

Just outside the staircase leading up to the building (now closed) that was built in 1859 to house Henry Shaw’s herbarium and natural history museum, I saw this. I must have seen it or passed it dozens of times but this morning was the first time I’d noticed it and then wondered about it. After doing a match image search on Google, I got some hits. Turns out it's a Victorian era boot scraper. Either etiquette or house rules must have called for gentleman of the day to scrape before entering the museum.

Just outside the staircase leading up to the building (now closed) that was built in 1859 to house Henry Shaw’s herbarium and natural history museum, I saw this. I must have seen it or passed it dozens of times but this morning was the first time I’d noticed it and then wondered about it. After doing a match image search on Google, I got some hits. Turns out it's a Victorian era boot scraper. Either etiquette or house rules must have called for gentleman of the day to scrape before entering the museum. Here’s another curious object that’s been appearing all over the botanical garden during the summer. No signs anywhere to explain what it is or what it’s supposed to do. Google image match doesn’t know either. The white objects are made of light plastic. They’re mounted on poles about four feet off the ground. Inside there are no moving parts, no electronic connections – just a dark-colored rod in the middle. Ideas??

Here’s another curious object that’s been appearing all over the botanical garden during the summer. No signs anywhere to explain what it is or what it’s supposed to do. Google image match doesn’t know either. The white objects are made of light plastic. They’re mounted on poles about four feet off the ground. Inside there are no moving parts, no electronic connections – just a dark-colored rod in the middle. Ideas?? Who but the keepers of a botanical garden would think of using a tropical plant from West Africa as the centerpiece of a container planting? This striking four-foot tall shrub is labeled ‘Red Flag’ (Mussaenda erythrophilla). My garden’s book calls it ‘Ashanti Blood.’ The common names come from the deep red bracts arranged in a toothy array around cream-colored flowers which were still in bud this morning.

Who but the keepers of a botanical garden would think of using a tropical plant from West Africa as the centerpiece of a container planting? This striking four-foot tall shrub is labeled ‘Red Flag’ (Mussaenda erythrophilla). My garden’s book calls it ‘Ashanti Blood.’ The common names come from the deep red bracts arranged in a toothy array around cream-colored flowers which were still in bud this morning.

Along the broad walkway leading the Conservatory is an allee of Paulownia tomentosa trees. The botanical garden where I usually walk has two of these ‘Princess’ trees. In the spring, they have tight clusters of orchid-colored flowers that light up the tree. Until today though, I thought these trees were novelties. They don't grow straight and they have branches that appear helter-skelter. But they do grow fast – up to 12 feet a year I’ve read. That makes them useful for quick-fix landscaping in places like restored strip mines.

Along the broad walkway leading the Conservatory is an allee of Paulownia tomentosa trees. The botanical garden where I usually walk has two of these ‘Princess’ trees. In the spring, they have tight clusters of orchid-colored flowers that light up the tree. Until today though, I thought these trees were novelties. They don't grow straight and they have branches that appear helter-skelter. But they do grow fast – up to 12 feet a year I’ve read. That makes them useful for quick-fix landscaping in places like restored strip mines.

Inside, this place is like none I’d ever seen. Conservatories in botanical gardens usually are focused on saving space. They’re heavily planted – intent on finding a space for every exotic specimen they can squeeze in. Instead here at Longwood visitors are greeted with a view of an expansive lawn. Grass, common everyday grass, definitely not exotic grass. Here space doesn’t matter. There’s enough to go around for the ordinary and the unusual.

Inside, this place is like none I’d ever seen. Conservatories in botanical gardens usually are focused on saving space. They’re heavily planted – intent on finding a space for every exotic specimen they can squeeze in. Instead here at Longwood visitors are greeted with a view of an expansive lawn. Grass, common everyday grass, definitely not exotic grass. Here space doesn’t matter. There’s enough to go around for the ordinary and the unusual. Since other varieties of camellias bloom from November through March and flower best when temperatures are cool, Camellia Azalea could be a breakthrough if it could be used as breeding stock.

Since other varieties of camellias bloom from November through March and flower best when temperatures are cool, Camellia Azalea could be a breakthrough if it could be used as breeding stock.

function seems to be to disguise what otherwise could have been a stark hallway with nondescript white doors on both sides that open into individual restrooms so large, so clean, so elegant that they deserve to be called comfort stations.

function seems to be to disguise what otherwise could have been a stark hallway with nondescript white doors on both sides that open into individual restrooms so large, so clean, so elegant that they deserve to be called comfort stations. Somewhere I read that Pierre du Pont was disappointed with vigor and spent look of some Australian tree ferns that he saw in a conservatory that he visited on his travels. He vowed if he ever got the chance, he could do better. Humidity is the key. So to accommodate their needs he built this sunken garden near the ballroom. The marble floor is usually flooded to provide the humidity the ferns need.

Somewhere I read that Pierre du Pont was disappointed with vigor and spent look of some Australian tree ferns that he saw in a conservatory that he visited on his travels. He vowed if he ever got the chance, he could do better. Humidity is the key. So to accommodate their needs he built this sunken garden near the ballroom. The marble floor is usually flooded to provide the humidity the ferns need.

For visitors like me who like to get close to plants, this water lily display is ideal. Some of the Victorias were so close to the edge of the pool that I could have reached out and felt the spikes along the side of their pads.

For visitors like me who like to get close to plants, this water lily display is ideal. Some of the Victorias were so close to the edge of the pool that I could have reached out and felt the spikes along the side of their pads. Included in the exhibit is this photograph of a colony of Victoria water lilies taken from space. A nearby sign says that the Victoria is the only plant on earth that can be identified from satellite imagery.

Included in the exhibit is this photograph of a colony of Victoria water lilies taken from space. A nearby sign says that the Victoria is the only plant on earth that can be identified from satellite imagery.

All of the fruit trees and grape vines are trained to grow on vertical trellises to make them easier to harvest and to get an increased yield in a smaller space.

All of the fruit trees and grape vines are trained to grow on vertical trellises to make them easier to harvest and to get an increased yield in a smaller space.